The mining rights in Serra Pelada were held by the Vale do Rio Doce company, which maintained a subsidiary on the site without exploiting the mineral. The company never managed to expel the prospectors from the region, and in 1984 Vale was approved to pay US$60 million in compensation for the gold extracted by the prospectors.

In 2001, the government granted the rights to the site to the prospectors, but in 2006 there was a standoff between the government, Vale do Rio Doce and the prospectors.

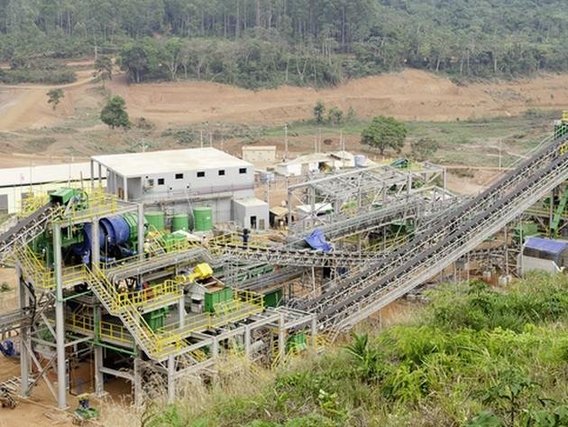

In 2007, the Canadian company Colossus Minerals signed an agreement with the Cooperativa de Mineração dos Garimpeiros de Serra Pelada (Coomigasp) to explore the Serra Pelada region. The contract stipulated that Coomigasp would have a 49% stake in the mine and Colossus 51%.

In 2009, the contract was modified and Colossus took a 75% stake. The company began making monthly payments to the cooperative, but most of the money disappeared. Following complaints, the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office investigated the case, and in 2012 the courts removed the head of the cooperative.

In 2013, Colossus Minerals faced a series of demonstrations by miners in Serra Pelada. The group was protesting against a change in the profit-sharing contract between the mining company and the cooperative. The repercussions of the project resulted in the change of several of the company's directors, including CEO Cláudio Mancuso, who resigned in November 2013.

Colossus even raised funds on the Toronto Stock Exchange in Canada, but the Serra Pelada project never got off the ground. In 2014, due to financial difficulties, the company went public and laid off its employees in Brazil. In 2016, Colossus permanently delisted its Brazilian subsidiary Colossus Mineração LTDA.

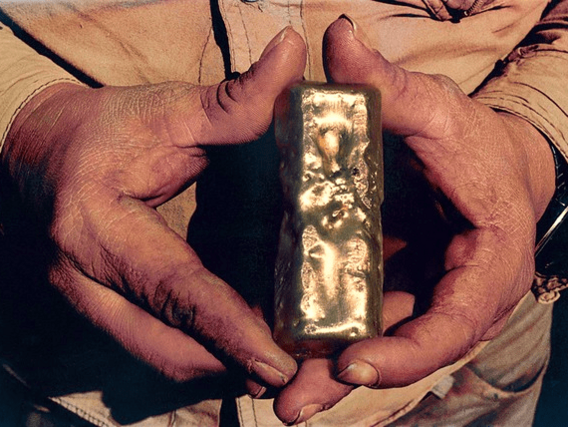

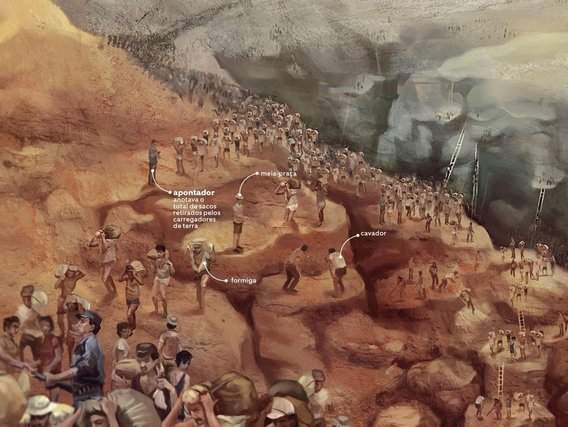

Serra Pelada was the object of interest for countless people looking to improve their financial conditions and help their families. Unfortunately, many people died in pursuit of enrichment. Although some people achieved economic success, the majority did not make any significant changes to their lives. Approximately 42 tons of gold have been extracted from the site. In addition, geological studies estimate that there are between 20 and 50 tons of gold still submerged under the lake.