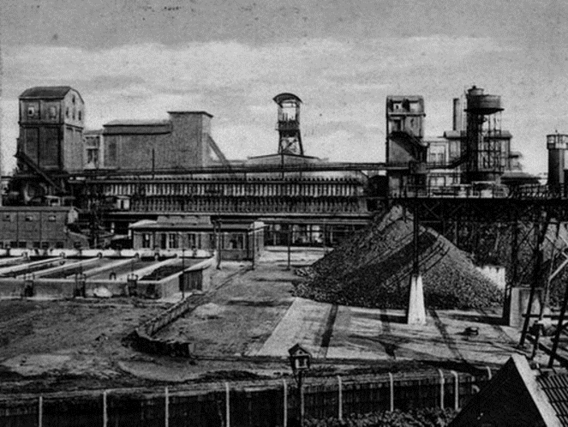

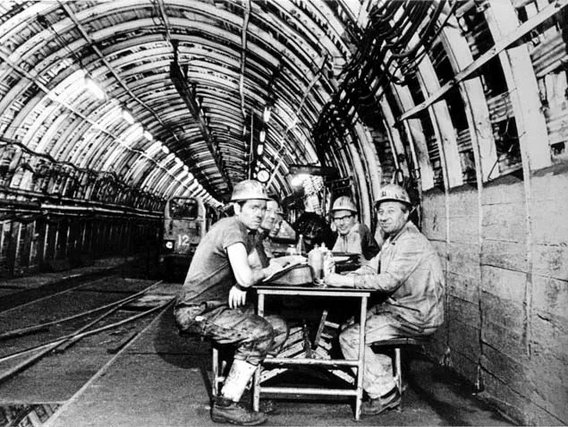

The Zollverein mine operated until 1986, producing around 240 million tonnes of hard coal. To reach this milestone, mining was carried out using the longwall method and was operated by more than 8,000 miners day and night in extreme conditions.

The closure of the Zollverein Mine involved a major effort to decommission machinery and equipment. One of the main challenges of the mine closure involved the drainage plan for the area and the extension of the pumping stations.

Since the mid-19th century, the Longwall underground mining method has been introduced in the Ruhr district. This method is suitable for mining bodies with a large lateral extension and a constant thickness.

The longwall is one of the safest methods for mining at great depths and its main advantage is that it allows for controlled subsidence, which can be accurately pre-assessed in terms of magnitude, effects and duration. The application of this method is the reason for the extensive subsidence observed in the Ruhr Valley.

The mining of more than 200 million tonnes of coal in Zollverein has caused the land surface level to drop by more than 25 metres in some areas. In addition, Zollverein is situated in the Emscher area, where many marshy areas already existed before mining began, and the subsidence caused by mining has significantly worsened these water flows.

A central pumping station is therefore in operation approximately 1,000 metres underground, pumping around 1,200 m³ of water from the mine to the surface every day. This process occurs in a similar way in several other Ruhr Valley mines; approximately 38 per cent of the Emscher catchment and 15 per cent of the Lippe catch ment are artificially drained. If the pumping stations in these areas were closed, most of the Ruhr district would be flooded

At Zollverein, the future use of the space was discussed at length with society, which decided to and conserve the site in order to maintain the installations that document the production process how the miners worked and lived.

Today, the architectural ensemble built at the Zeche Zollverein Mine demonstrates that the transition from industry to culture has been masterfully accomplished. After being listed, the entire mine closure was transformed into a large stage that keeps the history of mining and the development of industrial architecture alive.

The cultural routes, the architectural ensembles and all the history portrayed within the Zollverein Mine Complex can be found in our article "Zollverein coal mine complex: the transformation of a mine closure into a major architectural ensemble", where we tell you a little about the incredible cultural experience offered at the site.